Hitting a small round ball moving at high velocity with a thin round stick should be impossible, yet millions of batters successfully hit baseballs each year. The mere act of hitting a ball is well beyond the normal realm of human perceptual cognitive decision-making, which is the process by which the brain combines the various types of sensory information it receives to decide how to behave. A batter that can hit three out of ten is considered good; only Ted Williams hit .400 in a single season.

Batting .300 goes beyond simple reaction time – the hitter’s brain needs to make countless decisions in the blink of an eye.

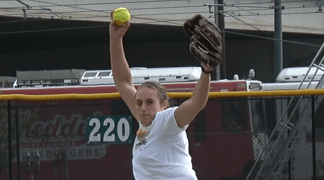

A baseball or softball pitch is incredibly fast, particularly when thrown by an elite athlete. A mere 400 milliseconds (ms) pass between the moment a pitcher releases a baseball to the moment it crosses the plate. The batter’s decision-making process occurs within the first 175 ms of the pitch – in the blink of an eye, the batter evaluates the movement of the ball then decides if and how he will swing the bat in response. Some hitters begin decision making before the pitcher releases the ball, judging by arm angle and the expression on the pitcher’s face.

While physical training helps give professional athletes the strength they need to hit a ball out of the park and to round the bases quickly, brain training helps batters connect with the ball more often and with more control.

About Brain Training

Brain training develops pitch recognition, improves quality at-bats, boosts on-base percentages, and ultimately increases runs. Quality brain training helps batters deflate a pitcher’s strikeout-to-walk ratio (K/BB) by increasing the hitter’s ability to contact every ball that enters the strike zone.

Brain training amplifies performance by practicing cognitive skills that affect athletic performance, such as visual processing speed and reaction time.

The human brain consists of special cells, known as neurons, which connect to one another to create a network. Fibers, known as dendrites and axons, connect the neurons. Dendrites bring information to the body of the neuron, while axons carry the information away from the neuron body. Repetition strengthens these connections to improve the way brain cells transmit information.

Repetition is the Basis of Learning

“Repetition is the mother of learning, the father of action, which makes it the architect of accomplishment.” (Zig Ziglar)

Being good at sports is nothing more than pattern recognition – a batter’s brain looks for patterns in the way a pitcher’s arm moves to predict how the ball will fly through the air. To recognize these patterns well enough to hit a baseball, though, batters must repeat the experience of hitting a baseball thousands of times.

Drill and practice is disciplined and repetitious exercise. Repetition improves speed, increases confidence and strengthens the connections in the brain. Strong connections allow information to move from the eyes to the brain to the rest of the body quickly.

Other types of cognitive training for baseball/softball help players respond to these patterns in ways that improve play. Stimulus response training can help players develop an automatic response to the patterns they see. This type of training improves motor imagery, a state in which the athlete imagines him- or herself performing a movement without actually moving. Stimulus response training can improve movement execution and baseball/softball reaction time. Repetition takes all the thinking out of it.

Training the brain and the body separately allows players to train each up independently. A player that has hit a plateau with physical training, for example, can advance his or her game through brain training.

New Technologies

Technology is now ubiquitous, seeping into every aspect of human health and activity. Since the day Abner Doubleday invented baseball in 1839 Cooperstown, NY, scientists and engineers have looked for new baseball/softball training aids, techniques and technologies to improve performance. Players have had to learn how to adapt to the evolution of baseball, and many use science to help them do that. The first few batters struggled to learn how to hit Candy Cumming’s curveballs, for example, but training and repetition taught the players how to recognize a curveball long before it leaves the pitcher’s hand. Training drills, particularly hitting and bunting drills, became mainstays in the NBA because they strengthen the fundamental skill sets that set a professional athlete apart from the rest.

Many of the basic training techniques and batting aids developed in the earliest days of baseball are still in use today. Players still use eye exercises, for example, in hopes of enhancing pitch recognition. A number of new technologies try to improve upon these basic training drills. Some add eye tracking to eye exercises, for example, while others offer fastball trainers that show you the dot in the slider. Technologies such as virtual reality (VR), video games and simulations in particular are sweeping through baseball and softball.

Not all tech is created equal, however – much of today’s technology is long on eye-catching graphics but short on substance. More realism does not translate into more learning. In fact, because the professional batter’s brain already has a reliable cognitive map of the batter’s box experience, realism may not even be necessary for effective brain training.

Furthermore, there is scant evidence that eye exercises, virtual reality or other modern training techniques actually improve performance behind the plate. Virtual reality in particular is a very young technology, so while VR is fun, its long-term benefits as batting aids are unclear. It is also expensive. Research may someday substantiate the use of these tools for baseball players, but there is currently no proof that many of the games and apps in use today work.

What researchers do know is that humans do not need to recreate every detail of an experience to learn. Sports specialists also know that tried-and-true testing and training methods, such as temporal occlusion, actually help hitters connect with the ball. These methods come highly vetted for all kinds of sport and non-sport specific tasks.

The long and short of it is, players should stick with those established baseball/softball training aids that work and are efficient, reliable, convenient and much less expensive.