Hitting Is Impossible

Softball hitting coaches love to say, “Hitting is hard.” I’m here to tell you that hitting isn’t hard. It’s impossible. Human vision can’t track fast pitches all the way to the bat. Getting square contact on a round ball with a round bat gives no more than a one-inch (2.5 cm) margin of error. And high-level pitches not only travel at speeds up to 70+ miles-per-hour (115 kph) but also move in unpredictable ways due to gravity, spin, Magnus effect, and other forces. It’s hard to argue with Ted Williams’ (the last major leaguer to hit .400) claim that hitting is “the most difficult thing in sport.”

So how do skilled batters not only hit well-pitched softballs but also hit them very hard and very far? It’s all workarounds. Hitters and hitting coaches relentlessly work on swing mechanics to generate bat speed and attack angles necessary to drive the ball. But they all will tell you that mechanics mean little without good timing to deliver the barrel of the bat to the ball at the optimal time and place in the hitting zone.

So where does timing come from? Stance and swing mechanics help hitters get two eyes on the pitcher, minimize head movement, get their front foot down “on time” and launch their swings in synch with the pitcher’s motion. But timing also involves pitch recognition. Good swing mechanics maximize the amount of time (and milliseconds matter) that hitters have to shut down their swing, if needed, or to make in-swing adjustments that get the barrel of the bat to the ball.

Pitch recognition is not as well understood or as frequently coached as swing mechanics. Therefore, pitch recognition is not only an important aspect of hitting but also is a way to gain competitive advantage by improving a part of hitting that your competition (including the guy next to you on the bench) is not. In this article I clarify what pitch recognition is along with why it is important. In a companion article I will get into when, where, and how to train pitch recognition.

What is Pitch Recognition?

It's probably more complicated than you think

It helps clarify what pitch recognition is by considering what it is not. Pitch recognition is not vision. Obviously, good vision is valuable for hitting and many major league hitters have 15/20 vision or better. But not all good hitters have superior vision, and not all hitters with superior vision are good hitters. In addition, while vision is correctable, it is not particularly trainable. On the other hand, visual skills such as convergence and divergence are trainable with a variety of devices and computer/smartphone apps (for example, Slow the Game Down and Visual Edge).

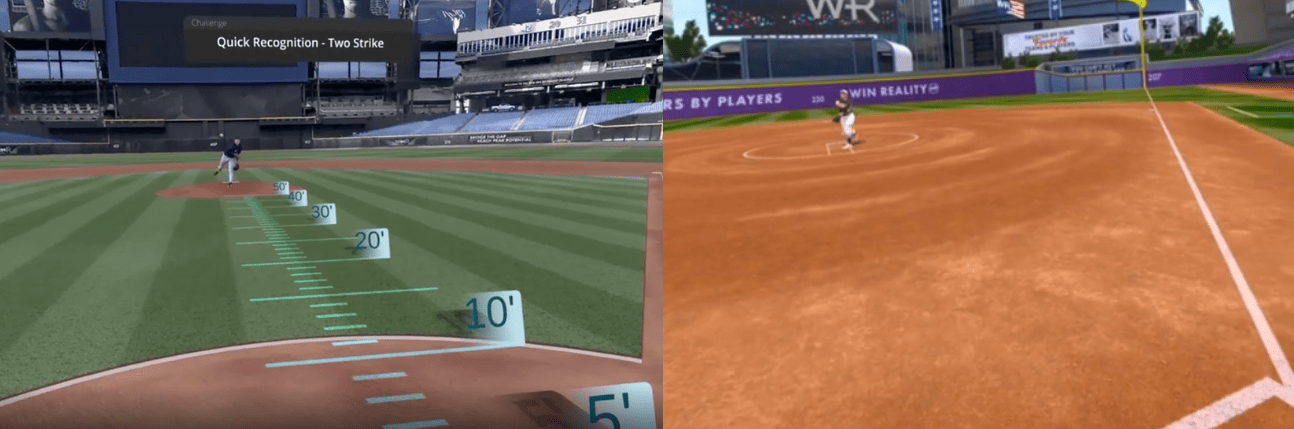

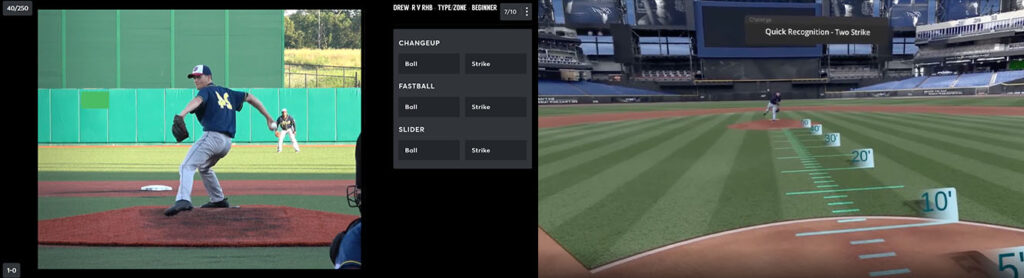

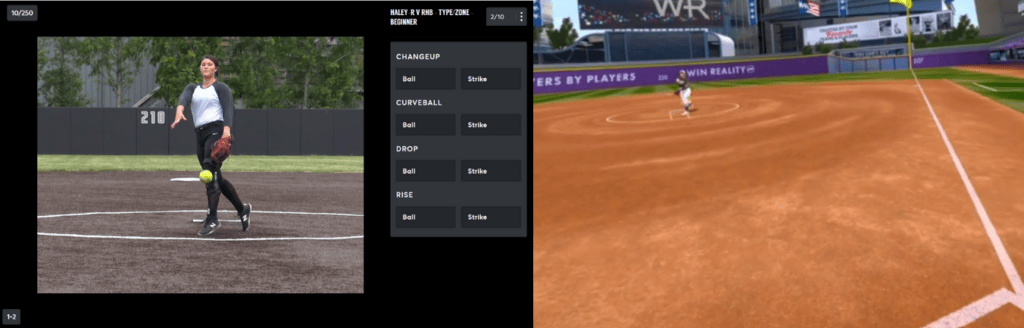

Virtual Reality (VR) is an another tool that doesn’t train or test Pitch Recognition

VR is good for perceiving the shapes of pitches and speed. But the computer models are not accurate or realistic enough to provide the necessary visual cues related to pitch recognition.

As important as visual skills are to hitting, however, it is a mistake to assume that training visual skills will automatically improve the perceptual skill of pitch recognition.

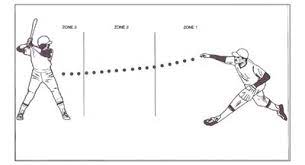

Perception is the meaning that you draw from what you see. It’s not “seeing” the pitch so much as it is “reading” the pitch. “Know the story of the pitch, know the story of the [bat] path,” says major league hitting coach John Mallee. The story of the pitch has three chapters, or Zones in this illustration from Harvey Dorfman’s Mental Skills of Baseball (applicable to Softball too):

Zone 1

Zone 1 is the MOST IMPORTANT part of the pitch. It includes pitcher’s motion, release of the pitch, and first 6-8 feet of ball flight. In this zone, hitters are able to read clues as to the type of pitch being thrown and potential landing spots. The earlier a hitter can accurately guess the type, speed, spin, and trajectory of a pitch, the greater chance of success.

For example, pitchers tend to adjust their body position in conjunction with the release and the ultimate trajectory of the pitch. Pitchers may lean forward slightly to enhance downward movement and conversely lean backward to enhance the rise of a pitch or actually straighten up when throwing a changeup. Some pitchers drift to the glove side when throwing a screwball or step across their body toward the arm side to throw a curve ball.

Other pitch release cues are hand placement including hand inside, behind or outside the ball. Pitchers put their hand inside the ball (backside of the hand facing the pitchers body internally rotated and in a supinated position) for riseball, screwball and lateral breaking curveball. Hand inside the ball is the only way to throw bullet spin. Pitches thrown with the hand behind or outside the ball result in tumble spin for fastball, drop, drop curve, cutter, peel drop change, inverted drop change, invert flip change, horseshoe release change or push release change.

Contextual clues are crucial to pitch recognition and come from repetitive observations associating these clues. A hitter must see and actual pitcher with actual pitches occluded to focus the brain to interpret variations with pitches recognized.

Zone 2

The beginning of Zone 2 is where hitters must initiate their swing. This is based on the pitch cues deciphered in zone 1. The hitter continues to take in and process visual cues. But processing takes time and the hitter can only make slight, late swing adjustments based on old information because the ball is moving fast.

Some hitters say they see the spin of the seams in zone 2, some say they don’t. More likely, hitters see spin clues. For example, some pitchers are taught two seam and four seam fastballs or drops. The two seamed pitch will show vertical train tracks as the seams align vertically while the ball spins. The four seamed pitch will appear blurred with some darker color concentrated toward each outer portion of the ball. But that these kinds of pitch clues are highly individual and many hitters can’t verbalize clues that their sub-conscious mind actually use.

More importantly, zone 2 is when a hitter can see the follow through mechanics of the pitch. Pitch follow through provides the next for hitters. Here are a few examples:

If the pitcher snaps their wrist downward over the top of the ball, the pitch will have tumble spin.

If the hand finishes on top of their forward thigh, it is usually a power drop, but if the hand continues forward with palm facing down, it is a tumble spin fastball.

If the hand crosses the forward leg with the thumb down it is a drop curve.

Many pitchers finish their follow through at shoulder height for a rise ball with their pinky finger leading their hand and the index or pointer finger pointing in the direction of the pitch (like shooting a make believe gun or snapping the fingers).

A horizontally breaking curve ball is most often associated with a “karate chop” finish of the pinky finger side of the hand along the belt line finishing along the front hip with palm facing upward. Some pitchers also point their index finger on their curveballs.

At high levels, hitters need to commit to their swing in Zone 2 with the pitch just over halfway to the plate.

Zone 3

Zone 3 is the hitting zone. The swing can no longer be halted. Hitters usually move their head and eyes down to the hitting zone as the ball enters Zone 3, but most do not actually see the bat meet the ball. Rather than tracking the ball to contact the head/eye movement is aiming ahead of the pitch like a bow hunter leading his shot. As Dusty Baker said in You Can Teach Hitting, “You hit the pitches with your imagination.”

Again, an illustration from Dorfman’s Mental Skills of Baseball shows the three “plots” that the story of most pitches follow (can be applied to softball):

Hitters’ brains unconsciously and almost instantaneously fill in the dots and mentally picture the shape of a pitch. Hitters automatically know the story of a standard, straight fastball (A) before it leaves Zone one. And their well-trained swing knows the story of the bat path to intercept it. Unfortunately, for hitters, pitchers manipulate the ball to “make strikes look like balls and balls look like strikes.”

This is where hitters’ brains draw upon their deep mental database of pitches to recognize patterns and connect the dots to either lay off the chase pitch (B) or to stay on the freeze pitch because it’s a strike (C). Pitch recognition is reading the story of the pitch as early and as accurately as possible in order to make better swing decisions and swing adjustments. Some hitters use pitch recognition to have good plate discipline – meaning that they swing at strikes and don’t swing at balls. But pitch recognition also is what makes selectively aggressive hitters impossible to pitch to.

When, Where, and How to Train Pitch Recognition

In this article, I covered what pitch recognition is (and isn’t) and why it is associated with the most dangerous and productive hitters. Hitters that aspire to next-level success, whether that’s making varsity as a freshman, playing elite travel ball, being recruited to play in college, or succeeding at the college level greatly increase their chances by consciously and conscientiously working on pitch recognition. And the earlier they start the better. In a companion article, I cover when hitters should start working on pitch recognition (ideally, before they need it), where to work on pitch recognition (team? instructor? facility?), and how hitters can work on and improve their pitch recognition.

References

Mallee, J. The Story of the Pitch; the Story of the Path, lead clinic at John Mallee Major League Hitting Clinics, 2020. https://www.majorleaguehittingclinics.com/

Dorfman, H. A. and Kuehl, K. The Mental Game of Baseball: A Guide to Peak Performance. Rowman & Littlefield Publishing. 1989.

Fadde, P. “The Sixth Tool: Training Baseball Pitch Recognition” (Amazon e-book). With citations from hitting books by Dusty Baker, Mike Schmidt, and Ted Williams.